A year has passed since my last adventure riding in the El Tour de Tucson, so it was time for this year's ride. 2015 marked the 33rd anniversary of this annual event, and once again I signed up to ride the full 104 miles. If I was going to subtitle this years ride, I would call it "The Ride That Almost Wasn't," but I'll explain what I mean by that a little later.

This year there were a couple of big differences from my ride last year, the biggest of which was that I rode with my friend Kevin, with whom I had recently ridden the 100-mile Cool Breeze Century. Kevin and I had been discussing the ride over the past few weeks, and I have been riding with a different philosophy - ride to have fun.

This may sound strange, but for the longest time I had been hating my rides. Seriously - I hated all of them. Of course, that is an untenable situation for someone who wants to be a recreational cyclist, so I had to figure out what was wrong with the way that I was riding. After some self-examination, I determined that my problem was simply that I was always racing the clock on each ride, and I was always trying to outdo my previous time. So a couple of months ago I decided to stop racing the clock, and I discovered that I was enjoying [sic] my rides a little more.

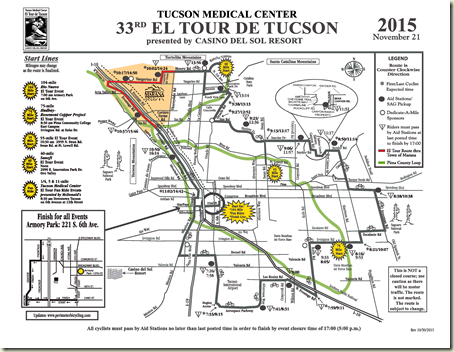

With that in mind, Kevin and I agreed to ride at a comfortable pace, and to stop for more of the Support and Gear (SAG) stops along the way. That being said, the El Tour de Tucson is an extremely well-supported ride with SAG stops every 5 or 6 miles, so we had plenty of opportunities to rest and refuel.

One of the bright spots about this year's weather was that it promised to be warmer than last year, which was literally freezing before the race started.

The 104-mile race starts at 7:00am, but seeing as how neither Kevin nor I wanted to race the clock, we agreed to meet at the starting point at 6:15am. (That was a whole lot better than last year when I got in line around 5:00am.) I woke up early, double-checked my pre-race cycling checklist, packed the last of my gear into the car, and headed across town to meet Kevin. As I drove across town I could see that the weather seemed to be pretty close to predictions, which meant that I wasn't going to freeze this year. (That was great news.)

I made it across town in short order, and I pulled into the parking lot at the Tucson Convention Center (TCC) shortly after 6:00am. TCC is near the starting line and has ample parking for lots of participants, so several cyclists were getting their gear ready as I parked and started to prep my gear for the day. I had loaded all of my equipment onto my bicycle, and as I was putting on the last of my cycling clothing I made a horrific discovery: I was missing my cycling helmet. (This is why I referred to this day's race as "The Ride That Almost Wasn't.")

Wearing a helmet is always a good idea, but in this specific instance it was imperative; the race mandates that all riders wear a helmet in order to participate. I mulled over my options, and I did a quick estimate to determine how long it would take me to drive home, pick up my helmet, and drive back. I might have been able to get home and back by the 7:00am start time, but as I was deliberating what to do, Kevin called me. I explained the situation, and after he had a good laugh at my expense, Kevin said that he could wait for me to get back before starting. I mentioned that the timing chips on our race placards do not start until we physically cross the start line, so starting a few minutes late might not be that big of a deal.

However, as the two of us talked, I saw that Kathleen was trying to call me, so I put Kevin on hold and answered Kathleen's incoming call. She found my helmet lying on the counter, and she was asking if she should bring it to me. Thankfully Kathleen already needed to be on that side of Tucson around 7:00am, so the two of us set up a place to meet somewhere near the start line. Once Kathleen and I hung up, I switched back to my call with Kevin, and I explained the arrangements to him. Kevin said that he would wait for me near the start line for me, then I locked up my car and pedaled over to Kevin's location.

After Kevin and I met, the two of us rode over to the place where Kathleen and I had agreed to meet, and she arrived around 6:40am. She quickly handed off my helmet, (see the following photo), then Kathleen headed off to her appointment while Kevin and I got in line for the race. (Note: I'm wearing a lot of cold weather gear in the following photo, but as the day grew warmer I slowly removed all of my cold weather gear.)

It was already 6:45am by the time that Kevin and I got in line, so we were understandably pretty far in the back. But still, neither Kevin nor I wanted to race, so our place in line meant little to either of us.

An unintended bonus from my earlier debacle meant that Kevin and I didn't have long to wait when we got back in line. (Which was a good thing since the temperature had dropped to 39 degrees.) After everyone had sung the National Anthem and a few kind words were spoken by the event dignitaries, the ride officially began at 7:00am. It took several minutes for the back of the line to start moving, but once we began to roll everything progressed in an orderly fashion, and we were on our way.

Here's a time-lapse video from the Arizona Daily Star of the race start; Kevin and I are in there somewhere... (We're on the far side of the street at 1:13, but good luck finding us!)

A little over a half-hour into the ride we hit our first adventure of the day - crossing the Santa Cruz River, which was thankfully dry this year. Nevertheless, it's always amusing to see hundreds of cyclists hand-carrying their bicycles across the dry riverbed. Although one of the best parts of this experience it is always the Mariachi band on the far side of the river.

Kevin and I rode through southeast Tucson along with the thousands of other cyclists who were participating in the 104-mile course, and yet we were able to ride close enough together to carry on a conversation as pedaled our way through the first several miles of the race. We met a lot of interesting people along the way, too. One of my favorites was a nice guy from the FBI who was riding his first century ride; we met up with him on the Houghton Road climb and East Escalante Road, (which are the last parts of a difficult climb to the highest point of elevation and we dropped him).

Thankfully I train on the east side of town all the time, so I ride Houghton Road and East Escalante Road several times a year. Another great part about hitting the highest point of the ride is that we get to ride downhill for several miles on Freeman Road.

About 3½ hours into our trek we reached the half-way point of the ride, which is also the second river crossing. We also took this as an opportunity for a short break, so we rested up, refilled our water bottles, and ate a few snacks. After that, we were back on our bicycles.

The next obstacle on our ride was the steepest climb of the day - East Snyder Road near North Rockcliff Road. Although it's the steepest part of the course, it is also thankfully one of the shortest climbs - perhaps only 200 meters or so. (But still, every year dozens of riders have to walk their bicycles up the hill. Neither Kevin nor me, though. Hehe.)

There's not much to say about the next couple hours of riding; we took advantage of a few rest stops, one of which was serving Eegee's frozen drinks. (Those were totally worth stopping for.) Once again - I hated the ride up La Cañada Drive, though.

When we were around 10 miles or so from the end, Kevin asked me how close we were to my time from last year, to which I replied, "Last year I had already finished the ride an hour and a half ago." (That seemed somewhat demoralizing for Kevin.) Nevertheless after 8¼ hours we rode across the finish line, and my second El Tour de Tucson was over.

|  |

| Kevin and I riding towards the finish line. |

Ride Stats:

- Primary Statistics:

- Start Time: 7:02am

- Distance: 104 miles (103.5 miles on my GPS)

- Duration: 8 hours, 17 minutes (6 hours, 58 minutes on my GPS)

- Calories Burned: 3,502 kcal

- Altitude Gain: 3,209 feet

- Speed:

- Average Speed: 14.8 mph

- Peak Speed: 31.8 mph

- Average Cadence: 78.0 rpm

- Temperature:

- Average: 65.6 F

- Minimum: 35.6 F

- Maximum: 95.0 F

- Heart Rate:

- Average: 143 bpm

- Maximum: 175 bpm

When I arrived home, I posted the following synopsis to Facebook: "How I spent my Saturday - riding 104 miles around the city of Tucson with 9,000 other people from around the world. This year I abandoned my usual habit of riding for time and I tried to simply have fun with it. Sure, it took me a lot longer than last year, but this year I didn't want to sell my bike when I was done... "

UPDATE: A few months after the ride, one of our local television stations put together the following video. There's a bit too much advertising from several of the corporate sponsors, but apart from that it gives a good overview of the event.