Not Everyone Can Do The Job

02 September 2025 • by Bob • Military, Opinion

I saw the following image earlier today, and I have to admit - I felt this way during my tenure in the military.

To be blunt, there were some jobs within the military that not everyone could do. But that had nothing to do with gender or race - it was a question of skills and abilities.

I didn't care if a man or a woman volunteered for any specific position within our armed services - as far as I was concerned, it only mattered if they could accomplish the mission. It didn't matter if ten people were needed for a mission and it took seven women and three men, or eight men and two women, or any mixture of white, black, Hispanic, Asian, etc. soldiers. What screwed things up was when I witnessed firsthand that DEI idiots were demanding that some roles needed to be "easier" so that a "more diverse population" could get in.

I saw a Warrant Officer argue against reducing the skills necessary to complete the Army's Air Assault program so that more women could pass the course. When he was accused of being a chauvinist he replied, "Combat isn't sexist. A bullet doesn't care if you're a man or a woman. The person standing next to you needs to know beyond a shadow of a doubt that you will be able to have their back when the time comes."

When we reduce the qualifications of certain jobs in the name of "equal outcomes," we jeopardize everyone's safety.

More 511th History: Being Punished for Planning Ahead

19 July 2025 • by Bob • Military

Here's another in my long line of 511th-related stories that I documented at one time or another.

Obtaining necessary items from supply was critical to carrying out our mission, and over the years we had a modicum of success with getting the clerks in supply to do their jobs and order what we needed. Throughout my first two years I learned how to anticipate what I might need in advance, and I would frequently requisition items from supply several months before I might need them, which often paid off handsomely. One item in particular that I always made sure our squad had an ample supply of when the 511th deployed to the field was "D" sized batteries, which the EW teams needed to run the AN/TRQ-30 radios by night. (The TRQ-30s consumed 12 batteries at a time.) Of course, "D" sized batteries were also used for our flashlights, so it was nice to have lots of spares.

But that being said, I vividly recall a deployment when the rest of the 511th hadn't bothered to plan ahead. When the time came to head to the field, a bunch of people ran to the supply office, where they were promptly informed that supply wouldn't have any batteries for several weeks - long after the deployment was over. Of course, a lack of batteries was insufficient to prevent the 511th from heading out to the field.

After our squad had arrived on site, word somehow got back to CPT Quinn that "SGT McMurray had a huge stash of batteries that he wasn't willing to share." Armed with that knowledge, CPT Quinn personally dropped by our location to put an end to what he perceived as my "greediness." When he showed up, he asked me to produce every battery that I had brought with our squad. I pulled out a couple boxes of brand-new batteries that I had requisitioned through supply, then I pulled out a large box of loose batteries that I had personally spent an hour checking with a multimeter before the deployment.

I proceeded to explain that - unlike the other squads in the company - I was constantly preparing for our next deployment. I always requisitioned new batteries months in advance, and I personally inspected every battery after we returned to garrison after a deployment. (Any battery with 1.5 volts was good enough to keep, and anything less was tossed in the garbage.) I also explained that the EW squads needed more batteries because of the TRQ-30s' unrelenting appetite for batteries, and I pointed out that many of the squads who were complaining about their lack of batteries generally wanted batteries for their personal boomboxes, which had nothing to do with the mission.

Nevertheless, CPT Quinn did not applaud my resourcefulness, and he confiscated half the batteries that I had faithfully accumulated over the months prior to this deployment. I tried to protest and say that a few nights without a flashlight might teach the other squads to plan ahead in the future, but my words - as usual - fell on deaf ears.

In case I haven't mentioned it elsewhere, CPT Quinn was kind of a jerk about these sorts of things.

![]()

PS - My devotion to planning ahead for our next deployment was due to having served with LTC Lesser, who taught the 511th to remain combat loaded at all times and ready to deploy at a moment's notice. CPT Quinn, however, did not share LTC Lesser's foresight and devotion to the mission.

Why we recognize Memorial Day

27 May 2024 • by Bob • Military, History

For those who are unfamiliar with his work, Ernie Pyle was an American journalist and war correspondent during World War II, whose frequent dispatches from the front lines with the troops let families on the home front know what it was like for their loved ones overseas. But more than that, Pyle's writing was unique, because he had a way of seeing things that were missed by others, and through his vivid descriptions of what he witnessed he could paint a picture for others to see the war through soldiers' eyes. Many of Pyle's journals read like poetry, which leads me to an entry he penned after walking the beaches at Normandy a few days after D-Day, which I think serves as an excellent reminder of why we recognize Memorial Day each year.

A Long Thin Line of Personal Anguish

Saturday, June 17, 1944

(From https://erniepyle.iu.edu/wartime-columns/personal-anguish.html)

NORMANDY BEACHHEAD, June 17, 1944 - In the preceding column we told about the D-day wreckage among our machines of war that were expended in taking one of the Normandy beaches.

But there is another and more human litter. It extends in a thin little line, just like a high-water mark, for miles along the beach. This is the strewn personal gear, gear that will never be needed again, of those who fought and died to give us our entrance into Europe.

Here in a jumbled row for mile on mile are soldiers' packs. Here are socks and shoe polish, sewing kits, diaries, Bibles and hand grenades. Here are the latest letters from home, with the address on each one neatly razored out - one of the security precautions enforced before the boys embarked.

Here are toothbrushes and razors, and snapshots of families back home staring up at you from the sand. Here are pocketbooks, metal mirrors, extra trousers, and bloody, abandoned shoes. Here are broken-handled shovels, and portable radios smashed almost beyond recognition, and mine detectors twisted and ruined.

Here are torn pistol belts and canvas water buckets, first-aid kits and jumbled heaps of lifebelts. I picked up a pocket Bible with a soldier's name in it, and put it in my jacket. I carried it half a mile or so and then put it back down on the beach. I don't know why I picked it up, or why I put it back down.

Soldiers carry strange things ashore with them. In every invasion you'll find at least one soldier hitting the beach at H-hour with a banjo slung over his shoulder. The most ironic piece of equipment marking our beach - this beach of first despair, then victory - is a tennis racket that some soldier had brought along. It lies lonesomely on the sand, clamped in its rack, not a string broken.

Two of the most dominant items in the beach refuse are cigarets and writing paper. Each soldier was issued a carton of cigarets just before he started. Today these cartons by the thousand, water-soaked and spilled out, mark the line of our first savage blow.

Writing paper and air-mail envelopes come second. The boys had intended to do a lot of writing in France. Letters that would have filled those blank, abandoned pages.

Always there are dogs in every invasion. There is a dog still on the beach today, still pitifully looking for his masters.

He stays at the water's edge, near a boat that lies twisted and half sunk at the water line. He barks appealingly to every soldier who approaches, trots eagerly along with him for a few feet, and then, sensing himself unwanted in all this haste, runs back to wait in vain for his own people at his own empty boat.

*

Over and around this long thin line of personal anguish, fresh men today are rushing vast supplies to keep our armies pushing on into France. Other squads of men pick amidst the wreckage to salvage ammunition and equipment that are still usable.

Men worked and slept on the beach for days before the last D-day victim was taken away for burial.

I stepped over the form of one youngster whom I thought dead. But when I looked down I saw he was only sleeping. He was very young, and very tired. He lay on one elbow, his hand suspended in the air about six inches from the ground. And in the palm of his hand he held a large, smooth rock.

I stood and looked at him a long time. He seemed in his sleep to hold that rock lovingly, as though it were his last link with a vanishing world. I have no idea at all why he went to sleep with the rock in his hand, or what kept him from dropping it once he was asleep. It was just one of those little things without explanation that a person remembers for a long time.

*

The strong, swirling tides of the Normandy coastline shift the contours of the sandy beach as they move in and out. They carry soldiers' bodies out to sea, and later they return them. They cover the corpses of heroes with sand, and then in their whims they uncover them.

As I plowed out over the wet sand of the beach on that first day ashore, I walked around what seemed to be a couple of pieces of driftwood sticking out of the sand. But they weren't driftwood.

They were a soldier's two feet. He was completely covered by the shifting sands except for his feet. The toes of his GI shoes pointed toward the land he had come so far to see, and which he saw so briefly.

Note: to read more of Ernie Pyle's writings, see Indiana University's online home for information and history about Ernie Pyle.

The Weekend Safety Brief

15 May 2024 • by Bob • Military, Humor

Throughout my eight-year tenure in the military, the "Weekend Safety Brief" was a common feature during each Friday's close of business formation, which took place before soldiers were dismissed for the weekend. Despite every attempt to be unique, I realized as I heard the disparate words from dozens of commanders, they usually said pretty much the same thing: "don't do something stupid and stay out of trouble."

With that in mind, the following summary briefing evolved over the years, which seemed to say everything that needed to be said:

"Don't add to the population.

Don't subtract from the population.

Don't do anything that will get you on the news or in jail.

If you end up on the news, own that sh** so you'll be talked about for years to come.

If you end up in jail, establish dominance quickly."

![]()

My Army Recruiter Never Lied To Me

24 June 2023 • by Bob • Military

Army recruiters have forged a dishonest reputation for their actions when they're trying to get potential recruits to sign up, and I will admit that sometimes that reputation is completely justified. Whether they're duplicitous recruiters who are trying to nudge indecisive candidates over the finish line when these potential recruits are trying to decide whether military life is right for them, or if they're overeager recruiters who are simply trying to fulfill their recruiting quotas, it is nevertheless true that some recruiters have no problems bending the truth when it comes to their recruiting tactics.

However, that wasn't my experience when I signed up, so I thought I'd share my story.

To be honest, I hadn't thought about joining the military at first, but my younger brother was joining the Marines, and one day he asked me to drive him across town so he could meet with his recruiter. At the time, the recruiters for all four primary branches of service - Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines - shared a single facility with separate offices. While my brother walked into the Marine recruiter's office, I walked down the hall to the Army recruiter's office - mostly to bide my time - and thus began a process that was to change my life forever.

The first step when joining the military is - obviously - meeting and working with a recruiter. As I mentioned earlier, Army recruiters have a bad reputation for dishonesty - which in many recruits’ situations is totally justified. For example, it was blatantly obvious that some of the recruiters in the Tucson office were lying through their teeth whenever they spoke to me. However, that wasn’t the case for the specific recruiter with whom I worked. My recruiter was always straightforward with me, and I’ll explain why he was being so honest in a moment.

The military has a list of available jobs, called Military Occupational Specialties (MOSs), which have designations like 11B, 19D, 12B. Before I met with a recruiter, I already knew about the 98G "Signal Intelligence Voice Interceptor" MOS from my stepfather, who had done that job for several years and enjoyed it. In a nutshell, being a 98G meant going to the military's language school for several months, then being sent somewhere (hopefully) exotic where you monitored people who spoke the language you just learned. That line of work sounded exciting to me, and when I walked through the door of the Army recruitment office, that was the only job that I wanted. I told my recruiter that I wanted to be a 98G, and I wanted to learn Russian. My recruiter said that he didn't know about selecting a specific language, and he couldn't guarantee any MOS until I took the "ASVAB Test," which I will explain.

The second hurdle for potential recruits when joining the military is taking the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB), which is a comprehensive test that measures all sorts of things and helps determine what you'll be able or allowed to do, and sometime within the next few days I headed to downtown Tucson to take this test. I had graduated high school a little over a year before, and I hadn't managed to forget anything over the ensuing months. With that in mind, I didn't find the ASVAB particularly difficult, and when one of the recruiters was giving everyone their scores after the test had ended, I was informed that I had scored a 98%, and the recruiter was stunned.

When I drove back to the Army recruiter's office, I was promptly informed that I could have any job I wanted, so the 98G MOS was mine for the taking – at least in theory. My recruiter informed me that there were two additional obstacles in my path: a thorough physical examination, and something called the "DLAB" (which I'll explain in a moment).

At the time of my enlistment, all physical exams for the state of Arizona were conducted at the Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS) in Phoenix, which was the main entry point for military recruits in the state. My recruiter arranged for me to travel by bus to the MEPS in Phoenix, and the Army put me up in a hotel on the night before my physical. On the following day I passed my physical for the most part, with a nagging medical issue that I needed to resolve before I could report for duty: I was horribly underweight. I had been an anorexic teenager, and I still weighed anywhere between 100 to 105 pounds on any given day. The Army made it clear that I needed to gain a few pounds before I could join.

The next item of the day was specific for the 98G MOS: I had to pass the Defense Language Aptitude Battery (DLAB) before I could become a military linguist. By way of explanation, the DLAB is an exceedingly difficult and very confusing test, wherein potential recruits are taught a series of artificial languages and submitted to a plethora of linguistic logic questions. The DLAB helps to determine – in theory – how adept potential recruits might be at learning languages. (Believe it or not, I learned some interesting things about languages during the DLAB that helped me later when I attended language school.) Nevertheless, my head was swimming by the time I was done with the DLAB. I thought that there was no way I could have passed that test, yet by no small miracle I did.

Having put both the medical physical and the DLAB behind me, it was time to meet with the recruiters at the Phoenix MEPS. They quickly outlined what my career would look like: Basic Training, Language School, Advanced Individual Training (AIT), then a tour of duty somewhere for my remaining time in service. Because the duration of my academic training would be almost two years, I would be required to sign away four years of my life. However, due to the high demand for my MOS, I had my choice between $32,000 for college when I left the military, or an $8,000 bonus upon completion of my training coupled with $10,000 for college.

The second deal that I was offered sounded good to me, and the recruiters had me fill out a "Dream Sheet" with my list of preferred language choices; I chose Russian, German, and French. However, the recruiters said that they couldn't guarantee that I would get any of my language choices, and I would have to take my chances if I joined. There was one potential pitfall to all this: if I failed out of any of my schools, I would belong to the Army for the duration of my four years, wherein I would have to do whatever job they chose for me.

I said that I needed to go home and discuss everything with my wife, at which point the MEPS recruiters dropped their sales tactics and shifted to outright mocking, with responses such as: "What??? You need your wife's permission to join???" Those guys were schmucks, but I stood my ground, and they eventually pointed me to the door. They made no offer to help me get home, they simply said, "The bus station is a couple blocks away down such-and-such street. Goodbye." To be honest, those jerks were so awful that it was almost a deal breaker for me. But then again, by that point I wanted to join, so I was kind of at their mercy, and I think they knew that.

And, of course, I did join.

When I arrived home and discussed everything that I had learned with my wife, we decided that my enlisting in the Army was really our best option for that season of our lives. I met with my recruiter in Tucson, and I signed up for the Army's "delayed entry" program, which allows recruits to formally join the military to lock in their MOS and the contract that they were offered, and then to report sometime later for duty (which could be up to a year). That being said, my "delay" was only a couple weeks.

And thus it was that on a clear day in the Spring of 1986, my recruiter drove my wife and me to the local MEPS for me to report for active duty. The time was still early, so my recruiter took us to a diner near the MEPS where he bought breakfast for the three of us. While we were eating, I asked my recruiter why he had always been honest with me, and he replied, "I knew that you were going to join from the moment you walked through the door, and I knew that if I didn't shoot straight with you, you'd probably change your mind."

He was right, too. I wanted the job, and I'm sure that he could sense that. However, I had also been a military brat for most of my young life, and I could spot recruiter BS a mile away. If I had thought that I was being deceived, I would have walked out the door and never returned. So my recruiter played it straight with me, and as a result of his honesty I was in Basic Training less than a month after I first entered his office.

In the years that followed, however, I had my life turned upside by incompetent clerks and jerks who incessantly ruined my life by failing to do their jobs correctly, thereby resulting in me being sent to the wrong unit because someone couldn't read my orders correctly, or being underpaid because someone couldn't do basic math, or temporarily losing my security clearance because someone didn't feel like filing the right paperwork at the right time, or having my family members suffer countless hardships as a result of my desire to serve, etc. The ocean of imbeciles whose myriad ineptitudes wreaked havoc on my life again and again will forever hold a place of scorn and contempt that wells up from the depths of my soul whenever I am asked about my time in uniform.

But my recruiter? To this day I have nothing but respect for the guy who helped me join. I'd love to shake his hand and say "thanks."

It's Memorial Day - Thank a Veteran

29 May 2023 • by Bob • Military, Opinion

An anonymous person posted a suggestion to social media that everyone should "Thank a Veteran this Memorial Day." I thought that proposal sounded like a good idea, so to all my former uniformed brethren - I say with a grateful heart, "Thank you for your service."

However, no sooner had the anonymous person posted their statement of gratitude, another well-meaning person responded with the following meme:

Giving benefit of the doubt, I believe the second poster's intentions were good, and I agree that wishing someone a "Happy Memorial Day" is culturally insensitive. Memorial Day is a time to remember and honor the sacrifices of our nation’s men and women who have fallen in combat. There is nothing that is "happy" about this annual observance, and as such the phrase "Happy Memorial Day" is at best an oxymoron, and at worst it is an insult to those who have lost loved ones during their time in service.

However, while I agree that we should NEVER utter the words "Happy Memorial Day" because they dishonor the meaning of that holiday, we can ALWAYS thank our veterans - whether it's Memorial Day, or Veteran's Day, or Independence Day, or Mother's Day, or Christmas Day, or a Tuesday, or a Friday, or any day that ends in "day."

In one fashion or another, every veteran has sacrificed, which is amply expressed by the following adage: "All gave some, but some gave all."

POSTSCRIPT:

For more information about Memorial Day, see The Tangled Roots of Memorial Day and Why It's Celebrated on the NY Times website.

More 511th Stories: Frustration and Flame Throwers Do Not Mix

20 April 2023 • by Bob • Military, Humor

A couple years ago I wrote about my memories of border duty on a cold winter's day, and earlier today I was thinking about a story that was related to those experiences. During my first trips to the former East German border during the winter months of the late 1980s, I'd drive my wife's and my vehicle on post when I got an alert call at zero-dark-thirty, and our car would remain in the parking lot at the 511th MI Company until I returned to garrison. However, being stranded in a tiny German village without a vehicle was less than ideal for a mother with two small children, so for a while my wife and I would wake up our daughters and pack them into the car, then the four of us would drive to the 511th, whereupon I would head off to the border while my wife drove home and put the girls back to bed.

This type of early hours lifestyle was hard on my wife and the kids, so as time progressed, my spouse and some of the other wives from either our church or the 511th worked out a plan to shuttle any stranded spouses on post to pick up their abandoned vehicles. When husbands returned to garrison, they'd call their wives to pick them up, and the couples/families would head home together.

I remember getting a "Lariat Advance" call on a dark, winter morning, and my wife rose to start her day as I was about to walk out the door. I said that I'd drive to post like we'd been doing in previous deployments, and my wife said that she'd arrange with someone to pick up our car in a day or two. I was on the border for a couple weeks, and when I returned to the 511th, I called my spouse to come fetch me. However, she said that the roads had been covered in snow for the duration of my absence and she'd never been able to pick up the car, so it was somewhere in the 511th MI CO's parking lot.

Of course, I was the one who had parked the car, so you'd think that I'd remember where I left it, but I didn't, and every car in the parking lot was buried under six to twelve inches of snow. After a half hour of searching, I finally located our vehicle, but then I was greeted by another rude discovery: the snow had melted at some point, and the resultant water had frozen into an inch of ice that was hiding underneath the snow. This meant that the car's windows and doors - and more importantly the locks - were frozen solid.

By this time it was evening, and darkness had already descended on the 511th. What I probably should have done was ask someone if I could crash in an empty bed in the barracks for the night, but I was tired from two weeks in the field, and I was cold, and I was hungry. All I wanted from life at that moment was a warm shower, a hot meal, and to sleep in my own bed. The only obstacle that was preventing me from achieving those reasonable requests was a frozen car door lock, which I was determined to fix.

I headed into the barracks and explained my predicament to a couple friends, and together we hatched a few schemes to try and rectify my situation. At first we chiseled the ice away from the lock, only to discover that ice had fully penetrated the lock's gears, so at the most basic level I couldn't put a key into the lock. I headed back to the barracks and grabbed a mop bucket from a maintenance closet, which I filled with hot water from someone's room in the barracks, then I hauled the bucket out to the parking lot and poured the hot water down the door. This didn't work, but I repeated the action several times hoping that each successive attempt would free up the gears a little more, but the lock refused to yield.

I should explain that the longer I stood in the cold trying to open the stupid car door, I grew angrier at my spouse for not having followed our plan to pick up the car sooner. However, if she had followed through, our car probably would have been sitting in our driveway with an inch of ice and six to twelve inches of snow piled on top of it, and my wife would have had to explain why there was no way for her to come get me.

I remembered a technique that I used to use when I was a teenager to kill spiders: you can use a can of Lysol spray and a lighter to create a low-tech flame thrower. I headed back to the maintenance closet in the barracks and grabbed a can of Lysol, then I borrowed a friend's lighter and headed outside to try out my latest scheme. As expected, the combination of Lysol and lighter made a perfect flame thrower, and I aimed the resultant flames at the frozen lock on the driver's-side door with the intention of finally melting away the ice. This didn't work, so I circled around to the passenger-side door and repeated my approach.

However, much to my horror, something entirely unexpected happened: the tiny plastic washer that was nestled between the lock and the car door caught fire; to be honest, I'd never noticed that plastic washer before. Adding insult to injury, even though I had immediately ceased my flame thrower activity, the fire from the burning plastic washer had already traveled inside the door, whereupon it quickly melted every bit of plastic that held the door handle in place, and the handle fell to the snow-covered ground with a discouraging and disgusting "clunk."

I stood motionless for a moment, then I'm sure that I uttered something profane as I realized what I had just done. To put things in perspective, the time was fast approaching 10pm, and I was still cold, tired, and hungry. My car was still encased in a cocoon of ice and snow - and I had just destroyed one of the two car door locks that were necessary for opening the vehicle. Once again, what I should have done was find somewhere to sleep in the barracks for the night, but I was determined to open the remaining

My actions eventually achieved the desired effect, and I was finally able to open the driver's-side door. However, I had to let the car sit and idle with the heater and defogger running at full blast for several minutes in order to melt away enough ice and snow for me to see well enough to make the long drive home to our tiny German village. I was still unjustly irritated with my spouse upon my arrival at our apartment, but after a warm shower and a hot meal and a night in my own bed, I realized that my wife would have been just as stranded as I had been the night before, but with less options to rectify the situation.

That being said, she probably wouldn't have caught one of our car's door handles on fire, either.

My Last Day in the Army, Part 2

21 February 2023 • by Bob • Military

I recently posted a blog titled "My Last Day in the Army," in which I described my misadventures during my trip to Fort Huachuca on my last day of active duty military service to pick up my final paycheck. However, there is one minor detail that I omitted from my narrative.

In the transition office, where soldiers pick up their final paychecks and take care of dozens of other mundane tasks that must be completed before they exit the military, someone had posted Saxon White Kessinger's semi-famous poem Indispensable Man on the wall. In case you're unfamiliar with it, this is what it says:

Sometime when you're feeling important;

Sometime when your ego's in bloom;

Sometime when you take it for granted,

You're the best qualified in the room:

Sometime when you feel that your going,

Would leave an unfillable hole,

Just follow these simple instructions,

And see how they humble your soul.

Take a bucket and fill it with water,

Put your hand in it up to the wrist,

Pull it out and the hole that's remaining,

Is a measure of how much you'll be missed.

You can splash all you wish when you enter,

You may stir up the water galore,

But stop, and you'll find that in no time,

It looks quite the same as before.

The moral of this quaint example,

Is to do just the best that you can,

Be proud of yourself but remember,

There's no indispensable man.1

In other words, despite many soldiers' years of patriotism, loyalty, diligent work and personal sacrifice, someone in the transition office decided to make it his or her personal mission to let every soldier who passed through the transition office know that they would not be missed, and nothing that they accomplished during their time in service meant anything.

Pardon my language, but the nameless person who posted that poem was an asshole.2

Footnotes:

- Saxon White Kessinger, "Indispensable Man," in The Nutmegger Poetry Club (1959). (Note that the author originally published this poem under the name Saxon Uberuaga.)

- I'm ex-military, and I still believe that occasionally there is no substitute for foul language.

My Last Day in the Army

09 February 2023 • by Bob • Military

As I neared my departure date from the Army, I had several weeks of leave remaining, and the Army offers soldiers two options for what to do with any leftover leave: soldiers can sell their unused leave back to the military, which makes for a nicer final paycheck, or they can take "Terminal Leave," which means that soldiers can continue to draw pay while essentially being out of the military. The extra money would have been nice, but I wanted out of the Army so badly that I opted for terminal leave.

In the days before I was to begin my final leave, several family members drove to Fort Huachuca to help my wife and me pack all our things into a moving van and drive to Tucson (where we stayed with family for a few weeks until we found a place to live). After my wife and I cleaned our former house from top to bottom and it passed inspection, we turned in the keys, and we were officially moved out.

When I was filling out my transition paperwork, the Army presented me with two options for receiving my final paycheck: they could mail it to me, or I could drop by the transition center on my last official day of service to pick up my paycheck in person. I had spent 8 years, 1 month, and 18 days in the military, and the one lesson that I learned throughout all my experiences was: if provided the opportunity, the Army will always screw something up. With that in mind, I knew that the Army would probably lose my paycheck if I had them send it to me, so I elected to pick it up in person.

As soon as my transition paperwork was taken care of, I finished clearing the required offices on post and turned in the last of my out-processing items. As far as the Army was concerned, I was gone. I began my terminal leave with nothing left to do except to wait for my honorable discharge to arrive in the mail and pick up my final paycheck.

However, the Army decided that they were making my transition far too easy for me, so they played their last card.

In the early dawn of a sunny day in May of 1994, I donned my Battle Dress Uniform (BDU) for the last time, and I made the 90-minute drive from Tucson to Fort Huachuca to pick up my final paycheck. When I arrived at the transition center, there was a long line of soldiers waiting to see the handful of clerks behind a series of fenced windows. (Imagine waiting in a single-file queue at the DMV, with no seats, and the apathetic or disgruntled civil servants are kept in cages.)

Most of the soldiers waiting in line were fresh out of Basic Training, and they were arriving at Fort Huachuca to begin their Advanced Individual Training (AIT). Because most of these recruits were Privates and I was an NCO, they would snap to attention or parade rest whenever I would walk by. This was endlessly amusing for me, although I had no desire for them to observe such formalities since I was essentially a civilian.

After a 20 to 30-minute wait, I was finally standing at one of the pay windows, and after handing over my ID Card I told the clerk that I was there to pick up my final paycheck. The clerk left to take care of that as I glanced around the tiny room where the service windows were located. There were perhaps a dozen or so new recruits in the queue, and a captain who might have been waiting on his final paycheck.

After a few minutes, the clerk returned and said apologetically, "I'm really sorry, SGT McMurray, but we mailed you your final paycheck." My voice rose significantly as I retorted, "But I told you that I wanted to pick it up in person!" The clerk replied, "I know - it was a mistake, and I'm really sorry." (You'd think I would have seen this coming, right?)

I knew that it wasn't the clerk's fault, but I couldn't resist having the last word. I turned around and faced the room of new recruits as I loudly exclaimed, "This stupid

As I descended the stairs in front of the transition center, I threw my BDU cap like a frisbee to my car (my aim was quite good that day), and I began taking off my BDU top as I walked through the parking lot. Somewhere in the back of my mind I was hoping that someone would attempt to challenge me for being out of uniform on post, but perhaps something in my demeanor let everyone else know that I wasn't in a mood to be trifled with.

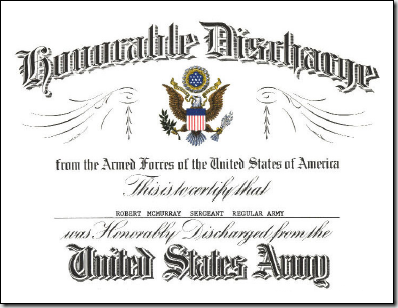

As expected, it took nearly a week for my final paycheck to find me, although I’m surprised that the idiots at the Fort Huachuca transition center didn’t try to mail the check to my former address on post (which would have had different occupants by then). However, sometime within the following weeks the following certificate arrived by mail, which meant far more to me than my final paycheck.

I Cannot Take Putin's Side in Ukraine

12 March 2022 • by Bob • Politics, Military

A well-intentioned veteran with whom I served in the military several years ago presented a challenge on social media: he asked everyone to consider information from all sides before deciding how to personally react with regard to Russia's ongoing invasion of Ukraine. To that end, he brought up a philosophy that we were taught in military intelligence: if you want to defeat your enemy, you must first understand him. This piece of wisdom can be traced back to the writings of Sun Tzu, and it is solid doctrine. My friend went further to say that listening to false intelligence about your enemy was worse than having no intelligence, because it could lead to fatal decision making. Once again, this is a solid piece of advice when considering world affairs.

Combining these two outlooks, my colleague shared the following video of a speech by Vladimir Putin, in which Putin asserts that his military aggressions over past two decades have been a reaction to NATO's eastward expansion. To paraphrase my former comrade's beliefs about Russia's invasion of Ukraine, he felt that Russia has just cause to feel threatened by the West because of NATO's continued expansion; therefore Putin's actions were acceptable - and somewhat inevitable - given the situation described by Putin in his speech.

However, I do not - and cannot - share my former colleague's opinion of this invasion. While my friend made a valid point that everyone should look at any given situation from all sides, that does not mean that every position has equal worth. With that in mind, here are some additional thoughts for everyone to ponder.

I watched Putin's speech in the above video some time ago, and I've heard when Putin expressed similar sentiments at other times. It's wonderful propaganda, to be sure, and Putin has outdone himself as a former member of the KGB with regard to his ability to spin his military aggressions as some sort of defensive posturing. However, his actions do not line up with the lies that he is telling. If you re-watch the above video and listen to Putin's version of events, he claims to be a peace loving individual minding his own business, while the West has been slowly threatening him. But if you ignore all the excess noise about NATO and the USA, what has Putin been doing for decades? He's been rolling his military into neighboring countries and grabbing up land and resources when neither NATO nor the USA have had anything to do with the situation. In other words, if some hypothetical person listened to Putin and believed his warped version of reality, that person is being played. Although to that hypothetical person's credit, they're being played by one of the most-skilled political manipulators to emerge onto the world stage. Putin is the kind of bully that will punch you in the face and then convince you that you need to apologize for it.

Here is something else to consider: does Putin actually care about the reasons that he is citing for his military aggression (like NATO expansion), or has Putin simply been given the opportunity of a lifetime to do as he pleases because he has a somewhat plausible reason for blaming everything he does on someone else? Consider the following PBS documentary from seven years ago, which documents Putin's rise to power from a lowly KGB agent through decades of corruption, embezzlement, and ruthlessness to become President of Russia.

Throughout Putin's ascendency, he formed powerful alliances with other corrupt politicians and oligarchs, from which Putin has personally profited handsomely. In addition, you might recall from recent years that Putin has no qualms about imprisoning or poisoning his political opponents in order to preserve his autocracy.

Like any good Soviet, Putin does a masterful job of committing atrocities and then blaming it on others. Here are a few recent cases in point:

- Putin accused Ukraine of hurting Russian separatists in the Donbas region, which provided him with his "justification" for attacking Ukraine.

- Putin has accused Ukraine of using chemical weapons, which - despite a lack of evidence - could provide Putin with his "justification" for using chemical weapons in Ukraine.

- Russian forces infamously bombed a maternity hospital in Mariupol, then blamed Ukraine for using the hospital to house neo-Nazis.

Putin is clearly using the same playbook that the Soviet Union used during the Cold War: the Soviets would accuse the West of doing something bad, which provided the Soviets with their "justification" for doing something bad themselves.

Harkening back to one of my opening statements about understanding one's enemy, there is a part of the collective Russian psyche that warrants examination: decades of post-WWII Russian fears about being invaded from the West - as Germany did during WWII - are not easily forgotten. This state of fear provides Putin with an excellent pretext to mobilize public sentiment behind any political or militaristic whim that he might concoct. In other words, Putin can claim, "I need to attack Govnovia because our security is threatened by the West," which he can use to conceal any actual intentions.

If you watch the following documentary, it describes how over the past few decades, Ukraine has continuously threatened Russia's profits from oil and natural gas, and sales of these fuel resources comprise 50% of Russia's GDP. Since Putin has made a career out of skimming billions of dollars from Russia, Ukraine's reduction of Russia's profits hurts Putin's pocketbook. Ergo - the true cause of Putin's actions is profits, and all his rhetoric about NATO and tapping into Russia's history of paranoia where the West is concerned is nothing but a smoke screen.

In summary, there was a grain truth to what my former colleague was saying when he pointed out that NATO has advanced eastward over the years. However, countries that have been recently added to NATO were not invaded militarily by the West. On the contrary, those nations asked to join NATO in order to avoid the exact scenario that is happening with Ukraine right now. However, let's set that aside for a moment, and consider the person who is claiming that NATO expansion is somehow a problem. As I said earlier, does Putin actually care? Or has the West inadvertently given Putin the ammunition that he needs to use military aggression to achieve his personal ambitions?

In the end, my colleague was correct when he said that one must understand his enemy and avoid false intelligence, and yet he has failed in both of those capacities: by accepting Putin's propaganda at face value, my former comrade has chose to base his worldview on false intelligence, and as a result he has failed to understand his enemy.

POSTSCRIPT:

In an ironic twist, Putin has become the same sort of dictator that Russia has feared; all of Putin's speeches about Russia needing to annex Ukraine sound just like Hitler's proclamations of needing "Lebensraum" prior to WWII. From my perspective, history is repeating itself in one of two ways: either Putin is attempting to rebuild the Soviet Union like his Communist predecessors (while personally profiting as a Capitalist), or Putin is making a land grab like the other infamous despot that I just named (and is therefore using the memory of Nazism to behave like a Nazi).